“Yes, it’s hard to write and publish a book like this with Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland and Freddie Gray and so many others no longer with us. Trayvon attended my sister’s church. His mother still does. These souls and racism are right here beside all of my messy evidence, past and present.” –Dr. Sharony Green, historian and author

Here, I continue an interview with Dr. Sharony Green of University of Alabama’s History Department for her book Remember Me to Miss Louisa: Hidden Black-White Intimacies in Antebellum America (Northern Illinois University Press; 2015; $24.95; ISBN: 978-0-87580-723-2). Part One of Dr. Green’s interview appeared last Monday in honor of Women’s History Month. Her book covers the many secret and slightly known relationship styles between black enslaved or freed women and white men who owned them and their children, throughout complicated regional webs in the South and parts of the North such as Ohio. In this segment of her interview, she discusses the gentle and precarious art of pursuing research through libraries and historical archives, her intellectual grounding from old South grandparents and her viewpoints on white men’s responsibility, or lack thereof, to the tragedies faced by women in America’s slave past.

PART TWO

Question: Again this book read like a suspenseful, dare I say, romance epic in so many parts it almost disguises the breadth of geographical analysis and even legal studies you give to truly explain how these affairs operated– very intricately, covertly, with codes and rules understood by most parties involved at all times. I feel like you were very close to these personalities’ stories. I know it’s probably super complicated, but please give just a peek into how you balanced all this information from so many different fields: history, science, agriculture, the law, industrialism, geography, etc…

Thank you for seeing how those fields do come into play and it was not by design. It just happened. I always knew law would be critical. After all, slavery was a legal institution. While at Chicago, I worked in the D’Angelo Law Library. Just being in that setting gave me an appreciation for how law works. I worked on the Circulation Desk, shelving and checking out books to lawyers, students, professors and the public. It helped me to see how modernity relies on rules even though our interpretation of them can be arbitrary. I once visited Richard Helmholz, who probably does not remember me. But he is as much a historian as he is a lawyer and law professor. His enthusiasm and careful way of seeing the possibilities of my topic was very encouraging.

I also received affirmation from Michael Conzen, who had no idea how much his instruction was helping me. I took the first and second sequence of his Historical Geography class. He helped me see how space mattered! He helped me find meaning in my earlier interest in maps. When I was a kid, my Mississippi-born grandparents would take us fishing to Lake Okeechobee and my grandpa gave me the map. I was the navigator. I would look up in wonder every time we approached a town that was on the map on my lap. Here I was a kid from Miami who was in rural parts of Florida, learning about the possibilities of travel.

With Conzen, I saw power in being mobile. We rightly look at the Middle Passage as a great tragedy. The same is true of interstate domestic slave trade. That is a horrible thing to be moved through space, forever separated from your loved ones. There is a competing narrative. The late Stephanie Camp, a brilliant scholar, did a wonderful job of borrowing from geographers and seeing the possibilities of “rival geographies.” In other words, enslaved women could see the same plantation space with different eyes. A forest looks like a place where enslaved people might hide if running away to a white slaveholder. To an enslaved person, it could also be a place to dress up and dance late into the night without the oversight of white people.

A cabin wall holding amalgamation prints recasts the slave quarters into a political space. Even if you can’t read, getting that print from some enslaved man who’d been on a ferry with some abolitionist – a possible ally who gave him that print – offered hope. It is the same kind of hope that existed in the wrinkled poster of the Kennedy brothers and Martin Luther King that was always taped to the wall of my late great grandmother’s living space in the late 1960s through 1993 when she died. No matter where she lived, that poster was taped to the wall. It was a competing narrative to all of the ugliness she experienced outside her home space.

So my work took into account that part of geography, but also allowance to see emerging urban life. Cincinnati was ground zero for ship making. Steam travel revolutionized how people and products moved through space, bringing what we now call the Midwest closer to the South and Eastern Seaboard. In the opening decades of the nineteenth century such movement and other developments, including the building of the Erie Canal, were critical not just for white Americans, but black ones, too. They either worked on such ships or benefited from servicing such travelers, even if the services provided were unfortunate exploitative moments like prostitution.

Question: In a Hollywood Reporter Roundtable interview Lupita N’yongo did before she won an Oscar for playing a less glamorous “fancy girl” in the 2013 film 12 Years a Slave, she said an eerie transformation came over her when the costume designer handed her actual slaves’ clothes to wear in filming. You are very respectful and careful to these people’s letters, noting how nicely their penmanship was and how they chose to end letters or how they declared their names and nicknames. How did it feel to hold these archived and preserved letters which helped you weave this tale? How did you get access to this rich network of photos, letters and even receipts?

Not all of those letters were written by the freedpeople or enslaved people themselves. In the case of the two women freed in Cincinnati, another African American woman wrote their letters. For sure, we see that woman, who was their landlord, writing two other surviving letters to their former master and the penmanship is exactly the same. Also, the final surviving letter from those women is in an entirely different handwriting. But it was indeed quite an experience holding these letters.

Initially, I accessed them via only microfilm. UNC-Chapel Hill sent them to Regenstein Library at University of Chicago. And there, I’d take them to a machine and read them till my eyes glazed over. But then, I got a chance to go to Chapel Hill and touch the letters. I thought doing so would make me tear up. Instead, I just looked away from the letters from time to time with the biggest smile on my face.

It was sort of like that now iconic line from Alex Haley (in Roots): “Kunta Kinte, I found you!” I was not as dramatic as I was when I fell off that chair in Regenstein [Library] after seeing the five letters on microfilm. It was a more quiet, even reverent reaction, as if I was sitting in the face of something huge. One white man, whether he intended to do as much, gave us a doorway to some important past when he saved these papers. Others did the same when they saved his papers.

There was something about one black woman and black women that was worth preserving. Did he imagine we’d see those letters? No. I often say if I met him in an alley in a sci-fi film, he may punch me unless he read the book and saw how I was concerned about the ethics of my research and how he actually got off easy. I don’t say he’s only vile. I say he was sometimes vile, but also complicated and in some instances, even generous. Who knew?

As far as access goes, much has changed. Back then, you needed to go in person or order the microfilm. These days, so much, including the letters and documents from the children freed in Huntsville, is digitized. You have to know where to look and be aware archivists are human beings. You cannot be demanding. Some are gatekeepers and may themselves be uncomfortable with your interest in certain documents. Some see the value in your work, but have to answer to many constituent groups.

We want to keep these libraries open and funded. It’s a fine line that we all have to walk until society has progressed to a point where more people are on the same page about telling these kinds of stories.

Yes, black Americans need to be unafraid to discuss our messy past, too, and be unfearful of people who tell us that we are doing it only in service of bigger narratives orchestrated by white people. My grandmother was never impressed with my research. She kept asking me what the big deal was. Yes, white men did things for black women even in her day. Those men weren’t angels and neither were the women. The men’s misdeeds were enormous, but wrong is wrong, she said.

My grandpa told me something similar. He said there are good and bad people in the world and not all the good people are black. That may make some people angry. But I’ll listen to two folks who actually picked cotton and lived through the Jim Crow period, people whose blood runs through my own veins, before I let someone else overintellectualize oppression. Wrong is wrong. The bandwidth and institutionialization of oppression needs critique.

Question: You withhold judgment throughout, as a scholar presenting your facts and evidence in neat chronology at a comforting pace. For whatever reasons, I did not condemn these white men in control as you wrote this. You go into black women’s alliances with white women one minute and oppression by white women the next. How was it for you as a black woman unearthing this history, where you describe the compartmentalizing of black women based on breed, pedigree, color and other factors? What advice do you have for anyone reading this on how to approach it?

First, let me say, I never let white men get off easy. A good many of them were scoundrels.

I discuss one Mississippi man who had relations with an enslaved woman named Maria, who was beaten so badly he thought she would die. Even in his letter to the man who apparently owned her, the same man who freed the two women and four children in Cincinnati, he was careful to protect the person who had beaten her. Without even waiting for their owner to give him permission, he relocated her daughter, who was likely his offspring, ““northward” to be educated, and there forever to reside.”

He serves as further proof that white men of this generation acted inconsistently and deliberately in their efforts to enhance and protect certain enslaved individuals, specifically women and children in whom they had earlier invested some measure of emotion. Yes, these men safeguarded their patriarchal and racial dominance. This man had not planned to protect all enslaved people from abuse or see to it that all enslaved children be freed and educated. He was concerned about two in particular. He treated most African Americans with indifference, but believed she and her mother deserved better.

Most of what I just said is verbatim from the book. I say it over and over again in the book with different white men. Historians, we have a way of repeating ourselves, that drives many readers crazy. But that kind of repetition – think of it as the chorus – is our thesis being thrown at you over and over again.

I am saying a generation of white men never emerge as angels, but they weren’t all devilish, or devilish all the time. Here’s why, I say. And then I share what I have learned.

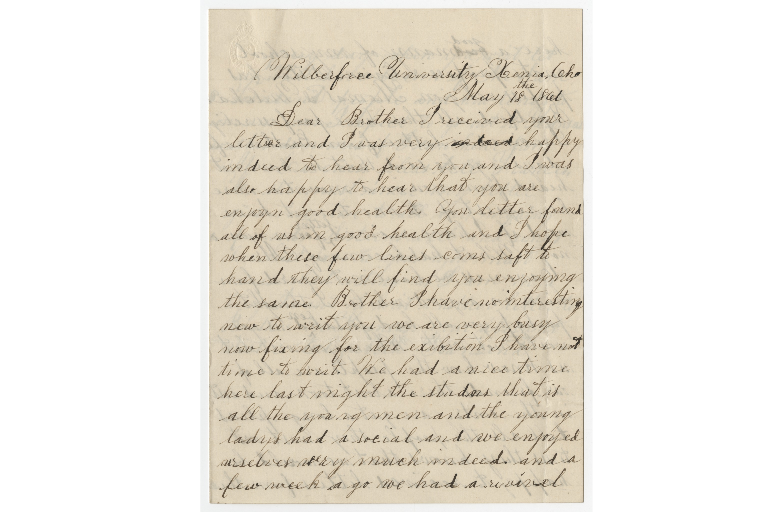

First page of 1861 letter written by Huntsville, Alabama’s Elizabeth Townsend, a girl of mixed race freed by her uncle’s lawyer on the eve of the Civil War. She is writing from Wilberforce, OH, where she and her sister as well as several cousins were relocated after also being freed. Sharony Green,Remember Me to Miss Louisa: Hidden Black-White Intimacies in Antebellum America (Northern Illinois University Press, 2015)

That said, I did have to press pause on seeing “Twelve Years a Slave” while writing this work. It’s still saved on my DVR. I will watch it this summer, with a bottle of wine. If I had seen it while I was researching and writing, I would have been back where I was when I first started writing that work of fiction in New York. I had messy characters, but still didn’t know enough to unflatten my view of slavery. Lots of potholes will slow you down if you are willing to pay attention. The horrors will be there.

Visual work, especially motion pictures, takes us to impossible places as Spielberg has said. But we can get so caught up in our emotions that we look other evidence in the eye and disregard it or disrespect it. Human beings are irrational creatures. It takes a lot for us to press pause and consider new bodies of evidence and consider how it changes everything we thought we knew about a person. The antebellum white male slaveholder was a piece of work, if you want to see him as the icon that he was and continues to be. But he was something else, too. What is that something else? That’s what I am inviting the reader to think about.

So as far as advice goes, my advice is offered in the context of people writing something difficult that may not be in line with larger narratives. Do so with caution, but don’t be afraid. Yes, it’s hard to write and publish a book like this with Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland and Freddie Gray and so many others no longer with us. Trayvon attended my sister’s church. His mother still does. These souls and racism are right here beside all of my messy evidence, past and present.

I have relatives who work in law enforcement. I have dear friends, too. They tell me about the complexities of their jobs. I hear it in their voices. My heart aches because there are so many sides to every story. But if you dare to speak them, you’re in for it. It takes real courage.

I tell my students, “It’s not always a black-white thing.” Sometimes it’s a class thing. Sometimes it’s an “I’m American-you’re not” thing. Sometimes it’s “I’m African and you’re African American or I’m West Indian and you’re African American.” Or “I’m Southern and you’re a Yankee.” We have developed so many ways to divide ourselves.

Consider the Freddie Gray case. Messy! Messy like my case studies although with critical differences that have to be carefully addressed. Historians are always careful in not saying “just like.” When I hear my students say that, I want to scream. Nothing is “just like” without some critical difference or differences.

Part Three of Dr. Green’s interview will appear Monday, March 28. In the meantime, enjoy the following WVXU-FM Cincinatti NPR interview where she discusses the role Ohio played in freed black women and children’s lives. You may also view historical letters and other materials at her history and cultural commentary blog on Tumblr, Remember to Miss Louisa.

A very good interview. Deep, and Very balanced answers. Appreciate very much the pains taken for the research. Hearty Regards, my Dear! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Yesudas! I appreciate you checking it. Yes, she is a great historian here and this book is really saying some things. I am glad somebody got it out there. Happy Easter! Kalisha

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank You, my Dear Kalish! You Are Appreciated! And Erika is Great too! Happy Easter to You and Yours, and Love. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awww thank you! She’s a good friend from the old days back home 🙂 Blessings and more blessings, Kalisha

LikeLiked by 1 person

Feeling Good with All those Blessings! The Same to You too, my Dear! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person