In the early months of 2004, E. Lynn Harris was the first major American author to send a blurb to my publisher based on the blue book of my first novel, Upstate. The novel was written by me, nobody author Kalisha Buckhanon. Nobody author had never sold a book. Nobody author had never done a book signing. I had just graduated from The New School’s MFA in Creative Writing Program. I had published one story, some essays and my bread-and-butter freelance journalism articles. I had won three small prizes for my unpublished fiction. I had not, besides a Publisher’s Weekly deal announcement and magazine bylines, had one media hit. I was 26 years old.

I had thought I was going to start sending out many rejected stories while working another little nobody job, eating up my paychecks to pay for manuscript copies or flirting the brothers in the mailroom into making and mailing my copies. But, a magical sequence of events led to the thesis for my master’s program circulating throughout the right hands. Shortly after I graduated school, it came to be that my words would become real books. And I received a telephone call to alert me that E. Lynn Harris had just called my little typed MFA thesis pages: “A literary gem.”

Huh.

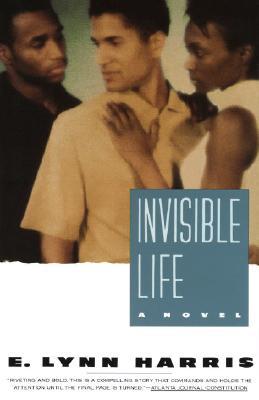

Everette Lynn Harris was born in Flint, Michigan, on June 20, 1955. He passed away in July 2009. He was a New York Times best-selling fiction author, a pioneer in that respect and second to perhaps only Terry McMillan at that time. He won the Lamba Literary Award for Anthologies and an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work in Fiction. Like a contemporary James Baldwin, he tackled the taboo subject matter of Black homosexuality with normalcy despite flair. The friend who first passed me a copy of his best-selling debut novel Invisible Life, which I never returned, was a similarly politically conscious and active student like myself. She told me: “Check out this guy writing for the gay brothers among us.”

I always look into the backgrounds of authors and their books, a practice which became frightening when it turned back onto me later. While some authors share my personality of media or public-shyness, Harris’s career served as a testament to the benevolence of artists to the public and media that make them.

I was not the only “nobody” author Mr. Harris lent his stamp of approval, faith and confidence to. I remember being so floored and excited by this news. My family was thrilled. I mean, here was an author they had actually heard of and seen the face of. Mr. Harris rarely, if ever, refused an invitation to read a Black novelist’s work and give them a quote. While the literary civilians of my life were starstuck with his endorsement of my work, I immediately learned some insiders would not be so impressed.

“Oh, he blurbs everybody!”

“Yeah, just print up a PDF and send it to E. Lynn Harris…you’ll have a quote!”

“It’s a strategy: remember, his name gets out there if it’s on a bunch of books.”

Huh?

Some other confusing voices went so far as to suggest Mr. Harris’s endorsement of my work would hurt my career, given he had been incapable of impressing white literary elite or winning mainstream literary prizes. This was my first introduction into the cutthroat narcissism and insecurity bred by such daring (and insecure professions) as the arts. E. Lynn Harris’s life and career teach us there is another way.

I decided to investigate all sides of the issue in this blessing the naysayers tainted. Call it the researcher and inquisitive Aries in me. As I had been warned, I discovered Mr. Harris did, in fact, blurb many authors all the time. Many authors make it clear online that they do NOT read for blurbs. Mr. Harris did, in fact, blurb a higher number of writers than I knew any other author to do. He did this while remaining one of the more prolific authors of any genre, race or gender. He also achieved this while maintaining a very busy public appearance and book signing record by most authors’ standards. He also accomplished this while teaching English, particularly African-American Literature, at the University of Arkansas, in a quiet and dusty pocket of the country where I was impressed a glamorous best-selling author would call home.

To first meet Mr. Harris (“Please, call me Lynn…”) in person, I walked into his book signing at Brownstone Books in Bed-Stuy Brooklyn, around the corner from where I was working on my second novel in summer 2006. He was dressed in an amazing suit with shining shoes and a glistening watch, so unlike I was at book signings; though my books were set in cities I was a country girl at heart, and I forced myself to at least wear ankle boot heels under the standard jeans and nice sweaters readers snapped me in. When he began to sign books, I introduced myself to him. He said: “Oh yes,” and gave me a big hug. Then, an invitation: “I want you to come talk to my students.”

In the corner of the bookstore, I recognized the unforgettable face of Bernice McFadden, one of the few novelists to receive a quote from Toni Morrison. Like Lynn, I met Ms. McFadden’s work “in passing”: the receptionist at my first job after college, as a secretary to a doctor (which helped me buy the nobody Chevy Cavalier parked outside of Brownstone Books), missed several phone calls across a week of reading McFadden’s Sugar on the job. She would not put the book down. I had confided in her and the primarily Black administrative staff that: “I’m writing a book.” I often snuck it in during my work hours.

Then, the receptionist lent me Sugar, “because you write.” I did, finally, give that borrowed book back. In between its pages, I saw a voice writing in the way I loved to read. From there, I bought The Warmest December and was further emboldened to pursue my fiction. Now, 6 years later in a bookstore in Brooklyn, Ms. McFadden had heard me introduce myself to Mr. Harris. She told me she thought she recognized my face as I had thought I recognized hers. I was unsure if to introduce myself to her, but I did. She immediately invited me to her brownstone in Bed-Stuy. She asked me if I liked wine and cheese. I told her “Certainly.” And then, as if I was not a nobody, she asked me what kind of wine and cheese I preferred.

Here was one big writer wanting nobody me to come talk to his students and another making sure to check with nobody me in a choice of wine. Over the summer, Bernice introduced me to her best friends and invited me to her daughter’s college going-away party. Then Lynn paid me a handsome honorarium to talk to his classes. And, Bernice was just as prolific as Lynn in her literary fiction as well as contemporary fiction under a nom de plume. Yet, all of my emails or calls were answered by both of them.

Huh?

What these authors were teaching—above teaching us how to write—was “How to Be: A Guide to Contemporary Living for African-Americans,” the title of Harriette Cole’s guidebook to etiquette, comportment and general social wellness. They were showing themselves as human beings with personas far beyond themselves, to the degree they had come face-to-face with a young woman who knew them through words they had spoken on the page. They were real and honest in those personas, as to revel in a chance to be themselves in the company of another “author” who might get it.

Lynn was, in his time, the Lady Gaga of novelists. He ate, breathed, lived and worked for his fans. His website appeared to be a love letter to us. He told me actually did answer all his emails. I know; he answered all mine. At some point during my visit to University of Arkansas via his coordination and orchestration (“Now, make sure they send you your money or you call me”), a little drama erupted at his home. It was about minding a child or ordering dinner or something. In an English Department hallway, he cut short our conversation to turn to his cell phone and try to settle it. He went on to me in a way which suggested the public E. Lynn Harris was the same in private: depended upon by many, overextended in self-generated tasks, and now putting a foot down with those who knew and loved him: “Listen honey, I can’t do it all.”

Around this time, author Bebe Moore Campbell passed away. They were friends, buddies, contemporaries, trailblazers in modern Black literature. As he walked me down a path to my campus hotel, he spoke to me about his anger and grief, as if I was an old friend. Little old nobody me. Perhaps he did not know this is how I felt. It did not matter. He made me feel 10 feet tall and I stand only 5 feet.

Although I had come to deliver some sort of lesson to his students, what I remember most was a lesson Lynn gave me before I departed. I am unsure how our conversation meandered to this lesson. We had trouble finding a place open to eat, and he was determined to respect my vegetarian life. He finally settled upon telling me to run up a room service tab in my small hotel. We had coffee in the lobby, during which he explained how I had seen the heart of him as a writer: a neo-Southern Detroit boy who now stood as a professor in his own class, with his “knucklehead” students he loved to challenge, and with authors such as me who were going to go places as well. He told me he had gone through phases in his success. His words echo to me to this day:

“I had an apartment in Janet Jackson’s building in New York, the suits, the watches, the cars. I was always on some beach. I was on the The New York Times best-seller list just for writing my name on my book. Then I was in a hotel on one of my tours. I had a lot on my plate, more than usual. Even I get stressed. I was starving, and they messed up my order in room service. It wasn’t enough for them to rush to get it right. I demanded to see a manager. When he arrived I said: “Do you know who I am?” And he actually did know who I was. That didn’t matter. I thought about it the next day, and said, “Who am I? What have I become?” It wasn’t me. There is a way to enjoy your success, but to view it all as blessings, and use it for God and for others at every turn.”

So, perhaps, this was the actual vision behind Lynn’s assembly line endorsements to nobody authors like me. After his epiphany, he began to invite a staggering number of Black authors to both cheer on his students at the University of Arkansas as well as be cheered on by them. He taught our books. And, yes, I was paid for my visit—early.

I would not see Lynn after 2006, though I kept watch on him and Bernice as mentors to turn to during the solitary crises every writer (and human) must face. He would send me information about grants and awards as well as teaching opportunities. I tried to make it to one of his Chicago events shortly thereafter, however I was inundated with PhD studies and fighting off a flu. Of course, I assumed I would see Lynn again. But in July 2009 I found out, from a cured Internet addiction first and phone calls next, that E. Lynn Harris had passed away in the prime of his middle-fifties.

Huh?

Some celebrity deaths flutter by as media fodder, public nostalgia or something to talk about. It is not that the loss of these names and faces means nothing to those who mourn them. It is just that the substance of the grief is largely content of our own makings.

Lynn, however, created the substance of our grief by his own makings—through his tireless activism on behalf of gay men and education, his commitment to his students, his support to not just Black authors but all authors, his true-to-life soap operas with thunderous messages of personal accountability, his smiling face on a welcoming website, his autograph at tireless book-signings. With author Marita Golden, he co-edited the anthology Gumbo: A Celebration of African American Writing, a “literary rent party” (in the spirit of Harlem’s infamous parties artists threw to pay their rent) to benefit the Hurston/Wright Foundation.

So, when someone like E. Lynn Harris is gone, there is the singe of a star fallen from the sky on every heart personally touched. He was a big brother and near father to many Black male authors. He was there for the women as well. If there was a club for African-American authors, I am quite sure he would have been elected its President. He taught all writers, and media figures in general, the value of appreciating your public not only through generic soundbites but through personal actions. If he had made it to the social media era, he would have smiled at every fan-tweet. He taught us humility and benevolence walk a thousand more miles than snobbery and mystery.

I would hope Mr. Harris would be extremely proud, today, of that young author he eventually met at a café in Brooklyn, then a book club conference in Atlanta and finally on the campus of his alma mater where she spoke to his classroom. I would hope he would be proud she taught her own “knucklehead” students. I would hope he would be proud to know she has never forgotten the strength of his generosities to her and the example it taught about how our smallest acts multiply to eternal power. I would hope he more often took the time when he was alive to be just as proud of himself as he tirelessly worked to be for so many countless others. He is so terribly missed.

20 Years Later: This summer Harlem’s famed Apollo Theatre will present the musical adaptation of E. Lynn Harris’s debut novel, Invisible Life.

E. Lynn Harris Bibliography from Wikipedia

- Invisible Life (self published 1991, mass marketed 1994)

- Just As I Am (1995), winner of Blackboard’s Novel of the Year Award

- And This Too Shall Pass (1997)

- If This World Were Mine (1998), winner of James Baldwin Award for Literary Excellence

- Abide With Me (1999)

- Not A Day Goes By (2000)

- “Money Can’t Buy Me Love” (2000) (short story), in Got to Be Real – 4 Original Love Stories by Eric Jerome Dickey, Marcus Major, E. Lynn Harris and Colin Channer (2001)

- Any Way the Wind Blows (2002), winner of Blackboard’s Novel of the Year Award* A Love Of My Own (2003), winner of Blackboard’s Novel of the Year Award

- A Love of My Own (2003)

- What Becomes Of The Brokenhearted – A Memoir (2003)

- Freedom in This Village: Twenty-Five Years of Black Gay Men’s Writing, 1979 to the Present (editor, 2005)

- I Say a Little Prayer (2006)

- Just Too Good To Be True (2008)

- Basketball Jones (2009)

- Mama Dearest (2009) (posthumously released)

- In My Father’s House (2010) (posthumously released)

Aw, this was great Kalisha. I never met E. Lynn Harris, but I miss him in my own way. I used to go to his website all the time, and was so impressed with his books. I read Invisible Life a couple times actually. I know he was pegged a “gay black author” and of course he was, but he was so much more. His work was just excellent, period.

A few years ago I interviewed an author (R.M. Johnson) and he told me about how much E. Lynn Harris mentored him and how much his support meant to him throughout the years. He actually credited Harris for changing the trajectory of his career since his endorsement meant so much at the time. They even co-authored a book (No One in the World) shortly before Harris passed.

Anyway, I’m glad that you got a chance to meet him, and it’s good to know that he showed you love. I see you constantly paying it forward and that’s a beautiful thing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hello Candance, Thank you! Yes, he was so much more. I remember that website. His personality definitely came through and it was the same behind closed doors as in front. That is a very rare thing. He was very generous with so many people and writers. Keep writing! Kalisha

LikeLike

And I”m a vegetarian too, and I fully understand your respect for him that he was considerate of you when finding a place to eat. I love it when people are respectful of me for that. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I may have missed your run-of-the-mill salad somewhere outside but I remember having a feast in the room! Blessings, Kalisha

LikeLike

I am going to see the Invisible Life The Musical at the Apollo Theater in NYC this summer. I can hardly wait. Here are the details if you are interested and able to go too: https://www.apollotheater.org/all/details/281-invisible_life_06_25-30_2015

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! I heard about that. Yes I was going to try to see it as well. Many blessings, Kalisha

LikeLike